Training or performing physical exercise has numerous health and mental benefits and must be a part of your daily life. It helps you build strength, speed, power, endurance, improve skill, build confidence and ambition, and improve self-esteem. It helps you gain knowledge about your body; how it performs, what are its physical and mental capacities, and how you could improve them. It also makes your body more resilient against injuries and illness.

Principles of training

Training is the practical application of science of sport and health sciences to improve the quality of life, improve athletic performance, reduce the risk of injury, and assist in injury rehabilitation. For training to be effective in achieving its desired outcome, few key elements, such as training intensity, training volume, training load, specificity, progression and periodization need to be in perfect harmony.

Let’s learn about some of the key principles of training and how you could apply them to your training to achieve your goals.

- Training Load or training intensity: Exercise is a stressor that produces physical and mental responses in the body. It is this stress that helps us adapt to training. For training to be effective, and for optimal adaptation, this stress needs to be appropriately controlled. This is achieved by careful application of training load. It has two variables:

- External load: This is determined by the organization, quality, and quantity of exercise. For example: in resistance training external load is the amount of weight lifted. Total work done, distance covered, or velocity achieved are other examples of external load.

- Internal load: Specific external load creates a specific internal load in the body (termed as psychophysiological response). Heart rate, skin color, sweating, genetics, nutrition, lactate threshold, hydration, and sleep are some examples of internal load.

Image showing training structure.

- Training Volume: Training Volume and load are inversely proportional. Meaning, as the intensity (load) goes up, training volume goes down. In resistance training, number of sets and repetitions represent total volume of training. Whereas, the amount of weights lifted in training intensity. A good training program should strive to strike the right balance between training load and training volume.

- Individuality: Every individual is different (anatomy, training age, genetics lifestyle), and training should be planned as per the individual differences.

- Specificity: Simply put, if you want to improve your 100 mt sprint, you shouldn’t be training like a marathon runner. Specific training induces specific responses, meaning your training should mimic the demands and skill of your actual activity or sport.

- Progressive Overload: In order to continue making progress, training demands placed on the systems of the body must be increased (overloaded) as they adapt and become capable of producing better performance (speed, strength, power and endurance). This is why training must always be progressive in nature, barring when the body is reaching the state of overreaching or overtraining.

Application of principles of training

Now that you know about some of the core principles of training, let’s learn how to apply the principles of training intensity and training volume to your training.

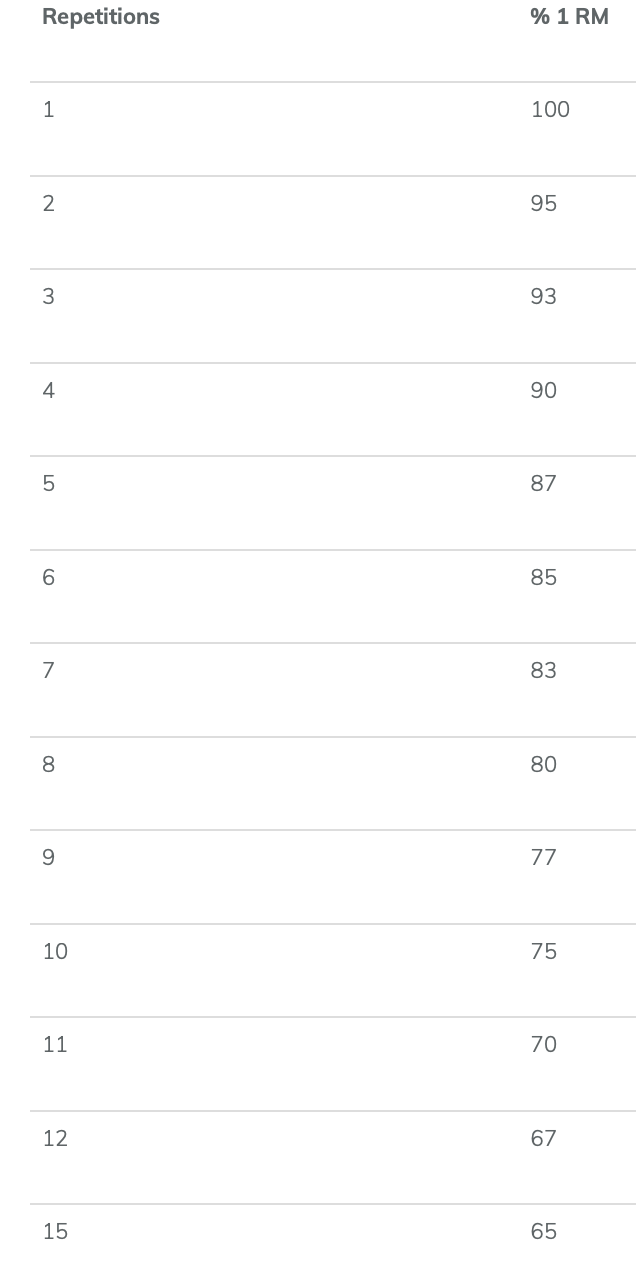

Volume is the number of sets and repetitions you perform. If you perform three sets of five repetitions, your total volume is fifteen repetitions. Volume and intensity are conversely proportional – as intensity goes up, volume reduces. It is humanly not possible to perform multiple sets or reps with one-rep-maximum load.

It is common to prescribe training volume on the basis of one repetition-maximum (1-RM). Here is how you can find your one repetition-maximum of a particular exercise. 1-RM strength could be predicted using repetitions-to-fatigue with a submaximal weight.

Beginners: 1-RM (kg) = 1.554 X 7 – to 10-RM weight (kg) – 5.181

Advanced: 1-RM (kg) = 1.172 X 7 – to 10-RM weight (kg) + 7.704

For example, estimate 1-RM bench press score for a trained individual whose 10-RM bench press is 70 kg as follows:

1-RM = 1.172 X 70 KG + 7.704 = 89.7 kg.

Image showing the relation between intensity and volume of training.

Ratings of perceived exertion: Another widely used and reliable tool for prescribing exercise intensity is Borg’s Ratings of perceived exertion (RPE). Developed by Gunnar Borg, the scale allows the user to rate how easy or how hord the exercise is, providing an indication of exercise intensity.

The scale goes from 1 – 10, 1 being absolutely easy, and 10 being maximal effort.

Image showing RPE scale.

Opposed to percentage-based training, RPE training accommodates daily stressors, such as sleep, work related stress, and nutrition, thereby giving the lifter a chance to avoid feeling burned-out.

If you are a beginner, performing 2-3 sets of each exercise with 10-15 sets per muscle group per week at an intensity of 60-80% is a good recommendation to follow. Gradually, as your body starts adapting to the stress of training, you could then focus on increasing the intensity of your training.

Whether you are an advanced athlete or a beginner, right from the very first time your training should alway be in balance when it comes to training intensity and training volume. It helps in:

- Reducing the risk of injury.

- Optimal adaptation to training.

- Optimal recovery.

- Avoiding the conditions of overreaching and overtraining.

- Keeping the process of training fun and motivating.

- Proper application of overload and progression.

References

1Current Sports Medicine Reports. Journals.lww.com. 2021. https://journals.lww.com/acsm-csmr/pages/default.aspx (accessed 21 March 2021).

2Impellizzeri F, Marcora S, Coutts A. Internal and External Training Load: 15 Years On. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2019; 14: 270-273.

3Coffey V, Hawley J. Concurrent exercise training: do opposites distract?. The Journal of Physiology 2016; 595: 2883-2896.

4BarBend Newsletter – BarBend. BarBend. 2021. https://barbend.com/newsletters/ (accessed 21 March 2021).

5Chen M, Fan X, Moe S. Criterion-related validity of the Borg ratings of perceived exertion scale in healthy individuals: a meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences 2002; 20: 873-899.

6Eston R. Use of Ratings of Perceived Exertion in Sports. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2012; 7: 175-182.

7ACE | Certified Personal Trainer | ACE Personal Trainer. Acefitness.org. 2021. https://www.acefitness.org (accessed 21 March 2021).

8Expert Strength Coaching + Free Content | Barbell Logic Online Coaching. Barbell Logic. 2021. https://barbell-logic.com (accessed 21 March 2021).

9Kasper K. Sports Training Principles. Current Sports Medicine Reports 2019; 18: 95-96.

10Lorenz D, Morrison S. CURRENT CONCEPTS IN PERIODIZATION OF STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING FOR THE SPORTS PHYSICAL THERAPIST. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015 Nov;10(6):734-47. PMID: 26618056; PMCID: PMC4637911.

11Bomgardner R. Rehabilitation Phases and Program Design for the Injured Athlete. Strength and Conditioning Journal 2001; 23: 24-25.

12Reiman MP, Lorenz DS. Integration of strength and conditioning principles into a rehabilitation program. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2011 Sep;6(3):241-53. PMID: 21904701; PMCID: PMC3164002.